Family Fun at Whangārei’s Kiwi North Museum & Heritage Park

- WORDS: HEATHER WHELAN

- PHOTOGRAPHY: HEATHER WHELAN

- PUBLISHED: NOVEMBER 22, 2021

Heather Whelan found there’s fun to be had for all ages at Whangārei’s Museum and Heritage Park, Kiwi North.

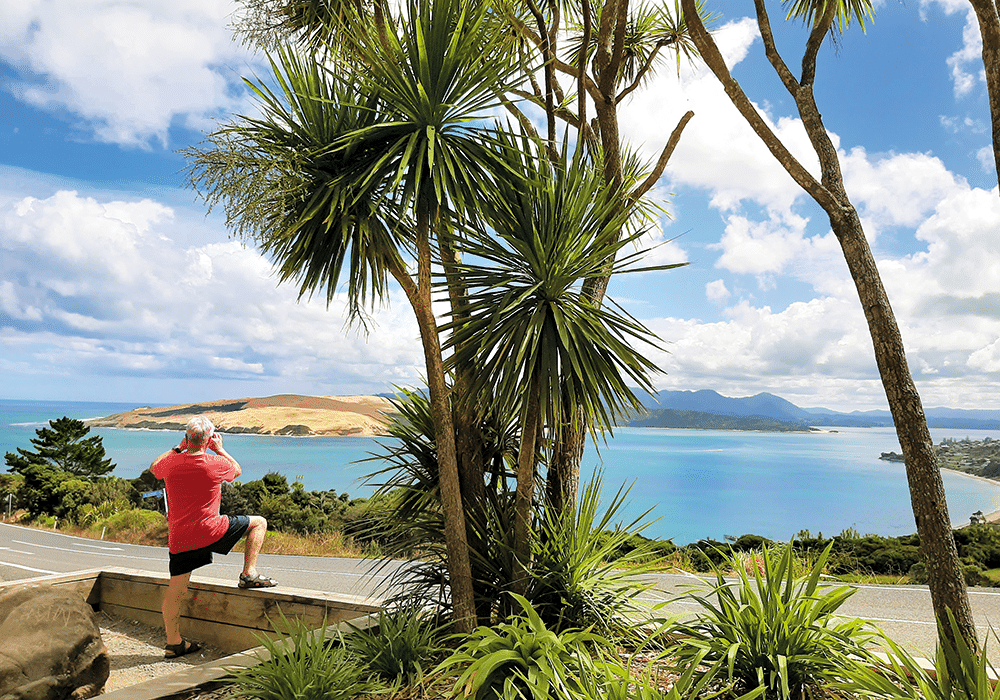

Just two hours north of Auckland lies Kiwi North, a 62-acre park that’s an excellent stop for travellers of all ages. Kiwi North’s mission is the preservation and conservation of natural and social history; if you’re an NZMCA member visiting Whangārei with littlies during the school holidays, or on the third Sunday of the month, you’ll be able to park up at a Park Over Property (POP) in the midst of the excitement of a live day.

If you’re more interested in a peaceful walk, then you can explore tracks in the 25 hectares of bush and farmland that make up the park. And if history is your thing then there’s plenty to discover in the museum and the nearby heritage buildings.

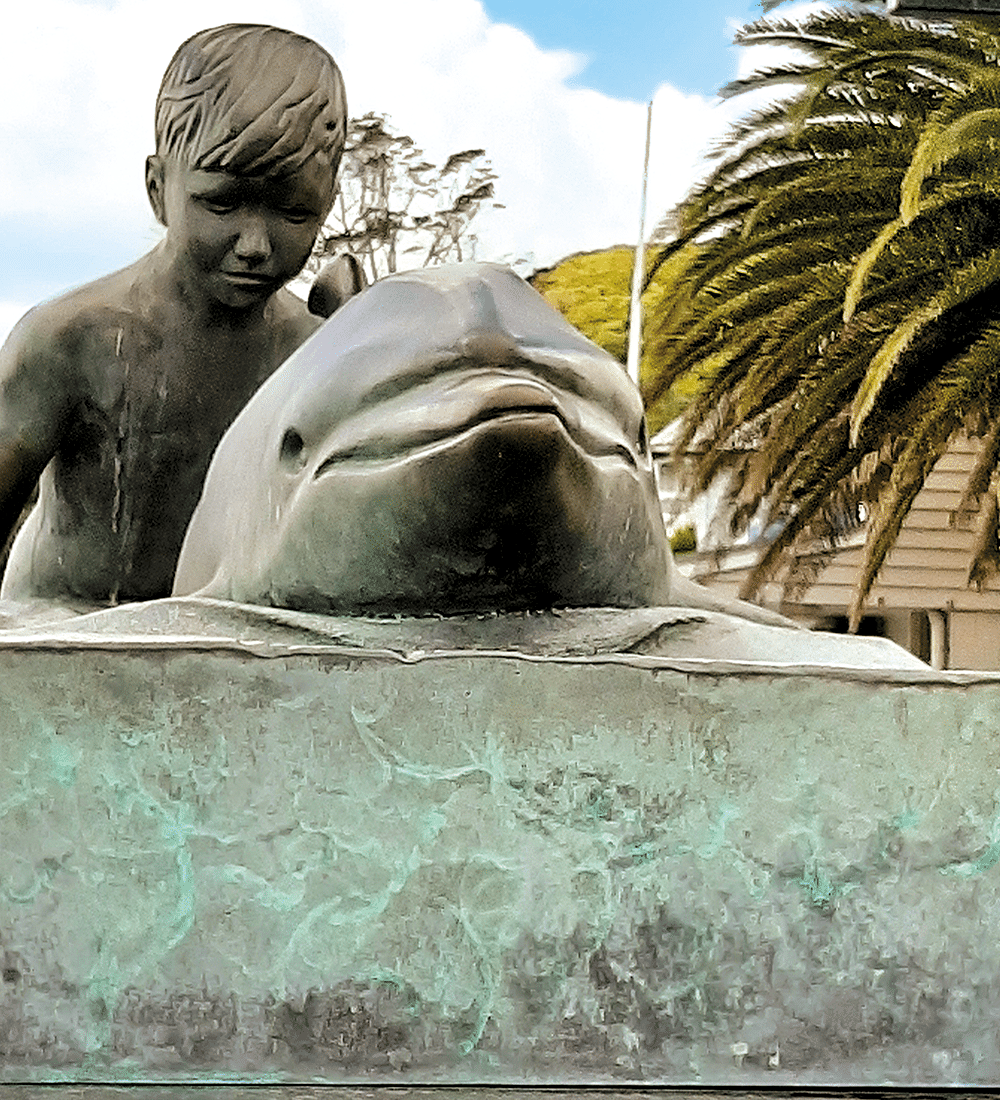

Kiwi and More

Kiwi North is home to Northland’s only nocturnal house. On our visit, we had visitors who were keen to see our national bird. Don’t be afraid to ask questions: Joey and Kevin at the reception desk have a wealth of knowledge and information about the kiwi, not only those in the kiwi house but also the ones that have been released into the adjacent Pukenui Forest. Before reaching the kiwi enclosure we spent a few minutes searching for different species of native gecko, cleverly camouflaged amongst sticks and twigs behind glass insets in the wall. There’s also a tuatara, who sat immobile and unblinking beside rocks, as his ancestors have been doing for the last 250 million years.

The kiwi house itself is kept in darkness during the day, so visitors can observe the birds in their nocturnal environment. When our eyes adjusted to the gloom we saw two kiwi foraging in their enclosure, using their long beaks like drills as they searched for food.

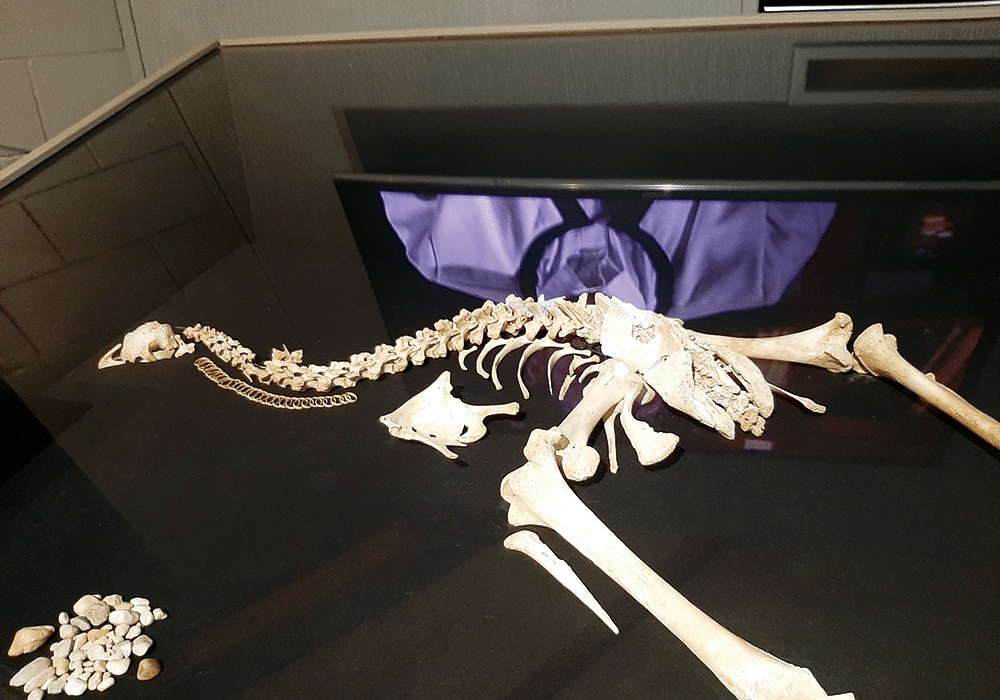

Moa and Muskets

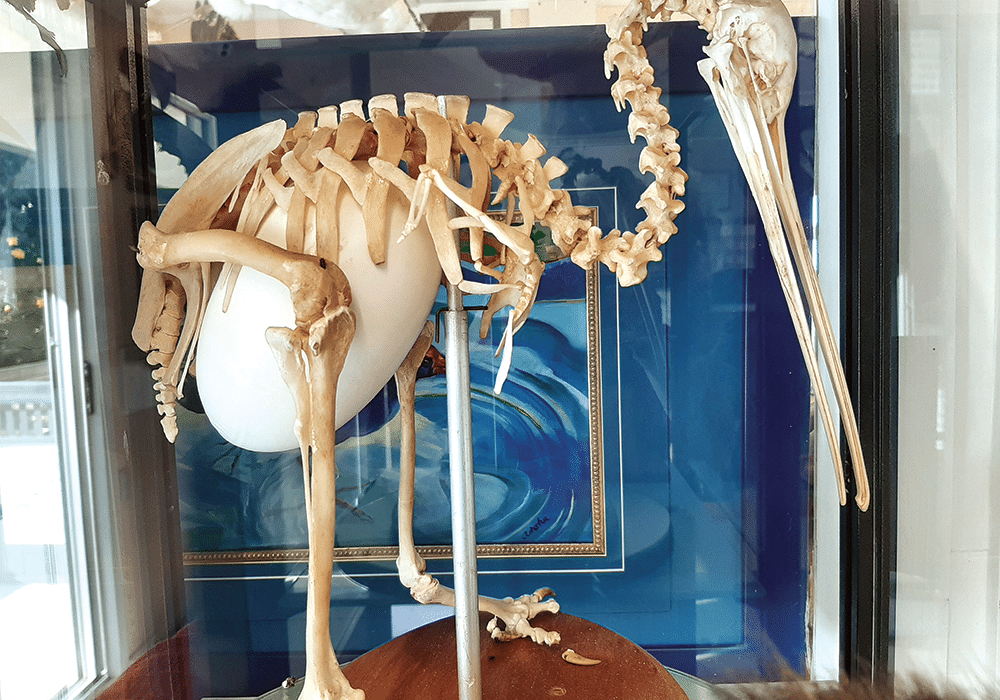

The Whangārei Museum is housed in the same building as the Kiwi House. Founded around 1890, there are over 80,000 items in its collection. We were fascinated to see skeletons of moa that had been discovered in a local cave, having lain there for more than 2000 years. There were also giant moa bones that had been found along the coast.

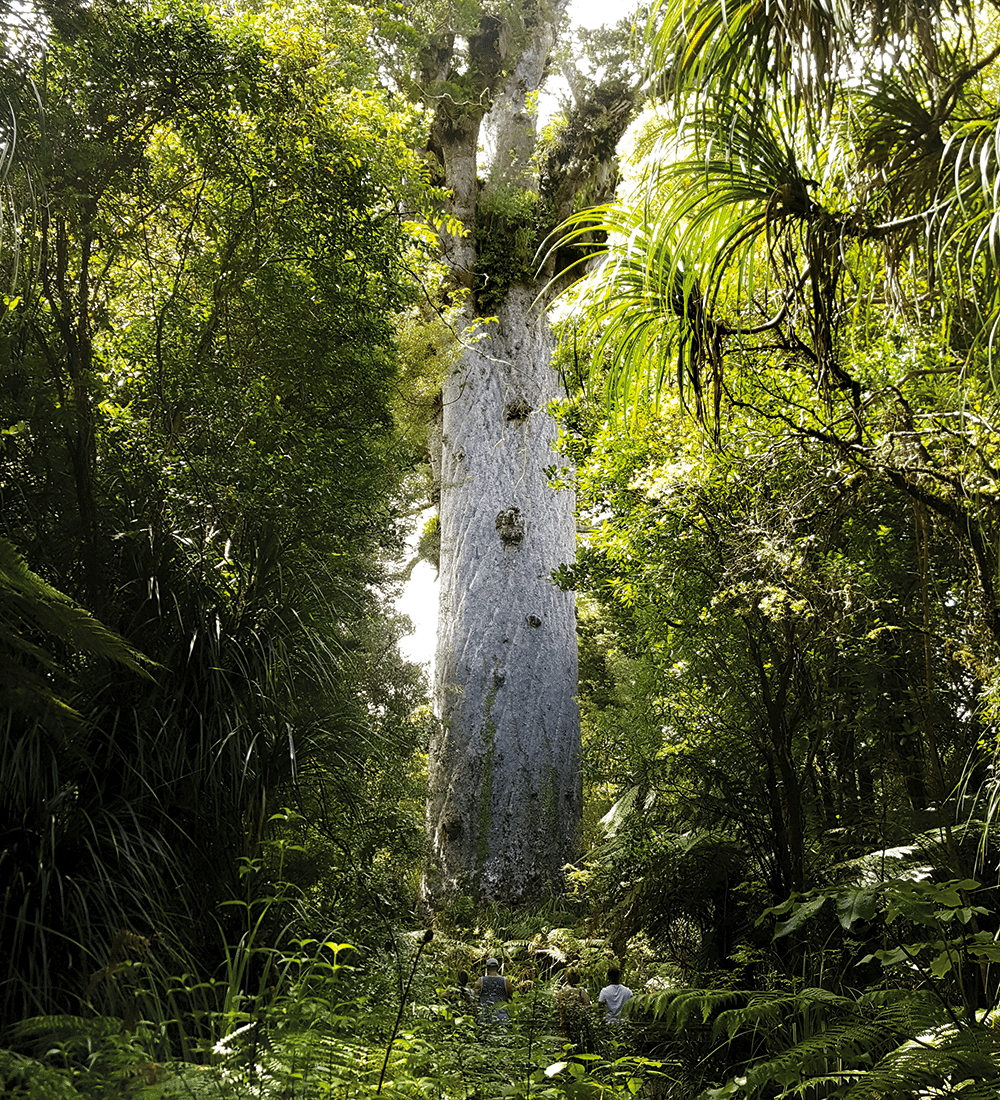

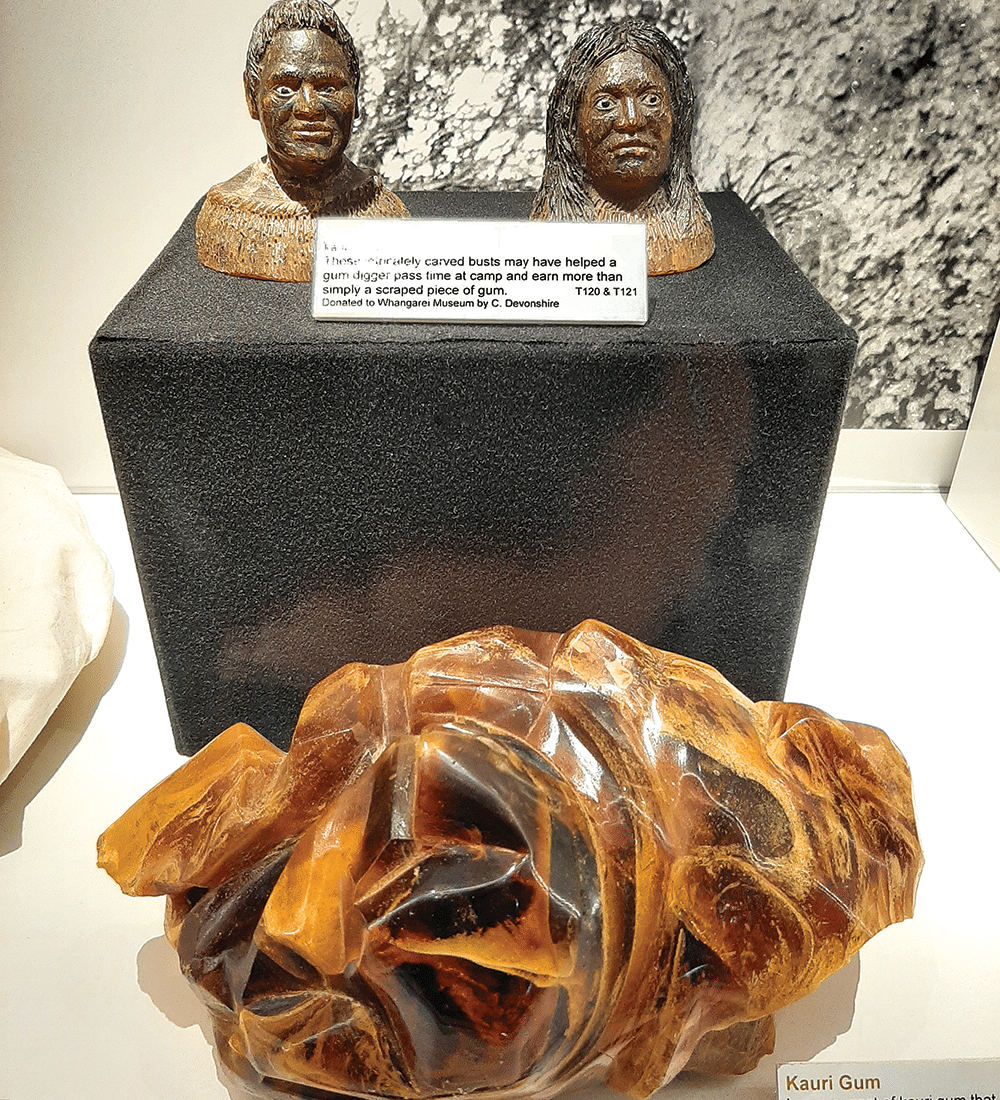

Nearby, two 300-year-old kauri waka were displayed. The larger canoe is a waka taua (war canoe) while the smaller one was made for river travel. There were also bone, stone and wooden artefacts, examples of Māori taonga. We were fascinated by displays related to gum digging, surveying and early settler life as well as military paraphernalia. We could have lingered longer but outdoor activities exerted their pull.

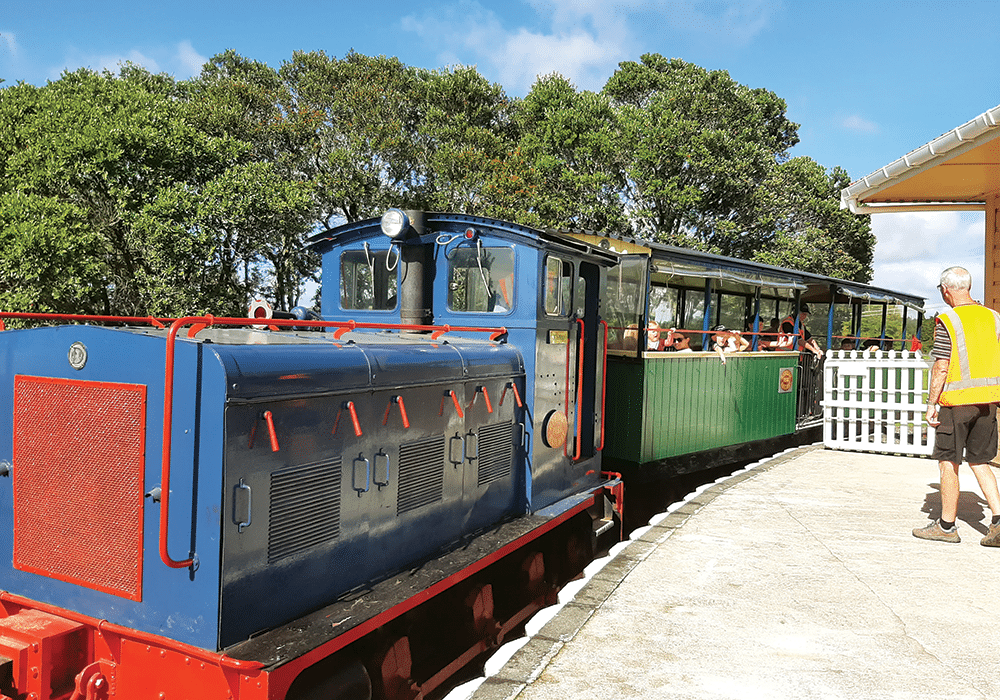

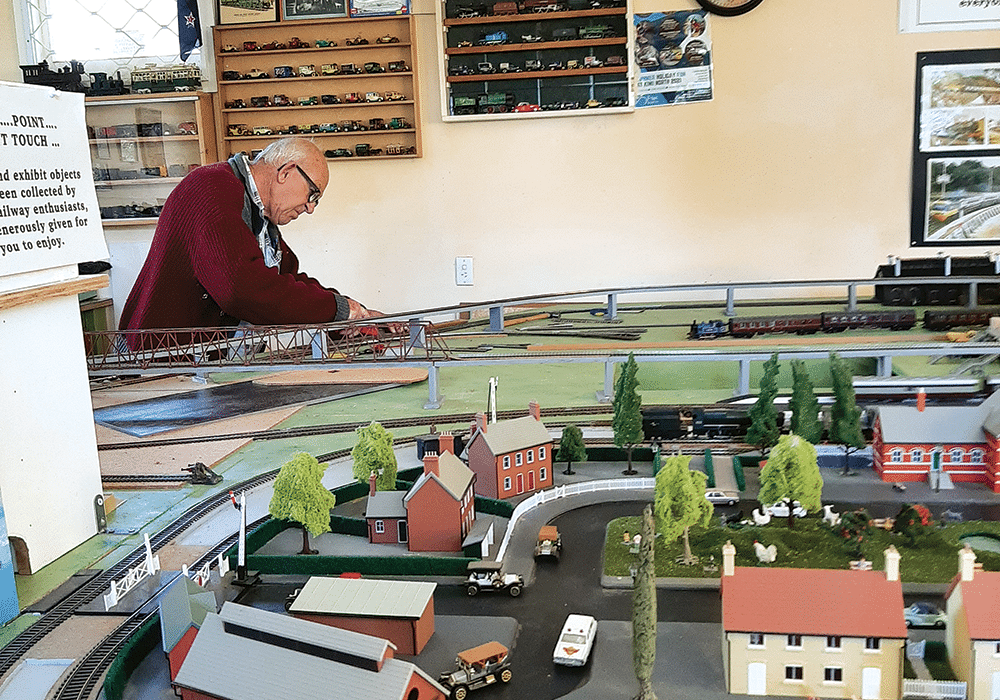

Trains Big and Small

Kiwi North is a train lover’s paradise; there’s something about a train ride that appealed to the child in us, as well as the excited children that gathered at the station. The Whangārei Steam and Model Railway Club at Kiwi North, and operate trains on special live days and holidays. We bought a ticket for ‘Johnny’, a diesel train, and checked out the model railway housed in the station building while we waited.

Soon we were rattling along the tracks to Millington Bush station, at the end of the line. En route we passed the mini train, built by the Whangārei Model Engineering Club.

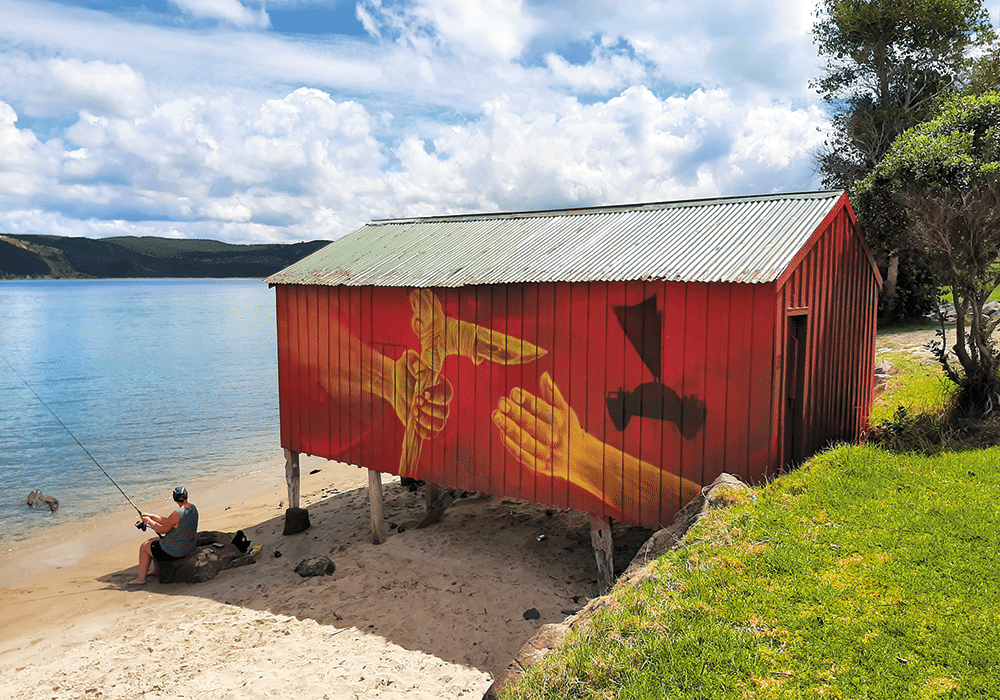

Clubs Galore

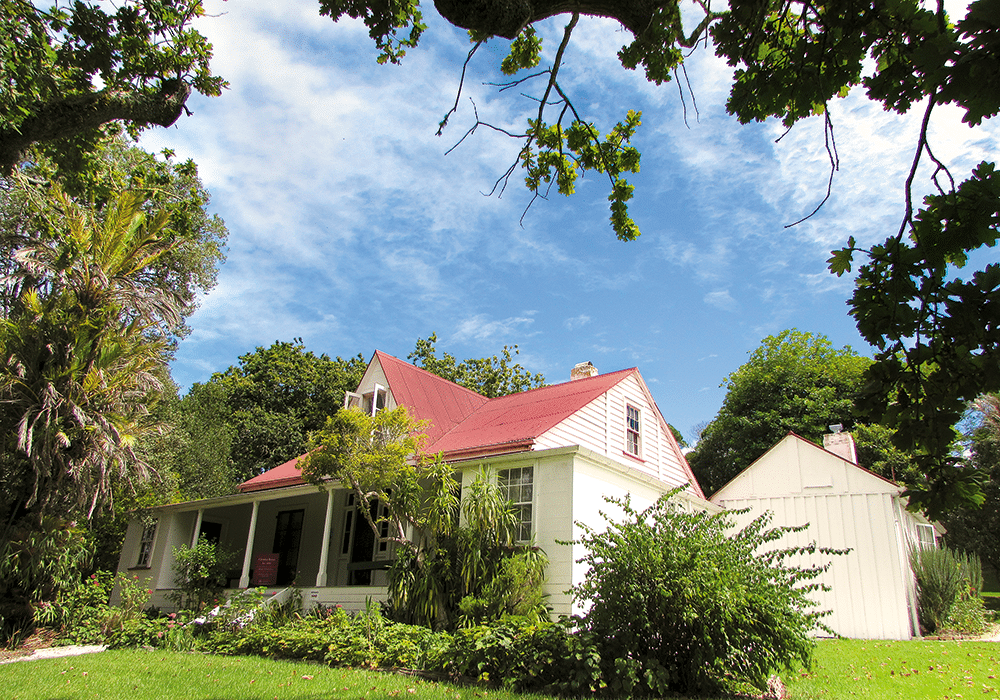

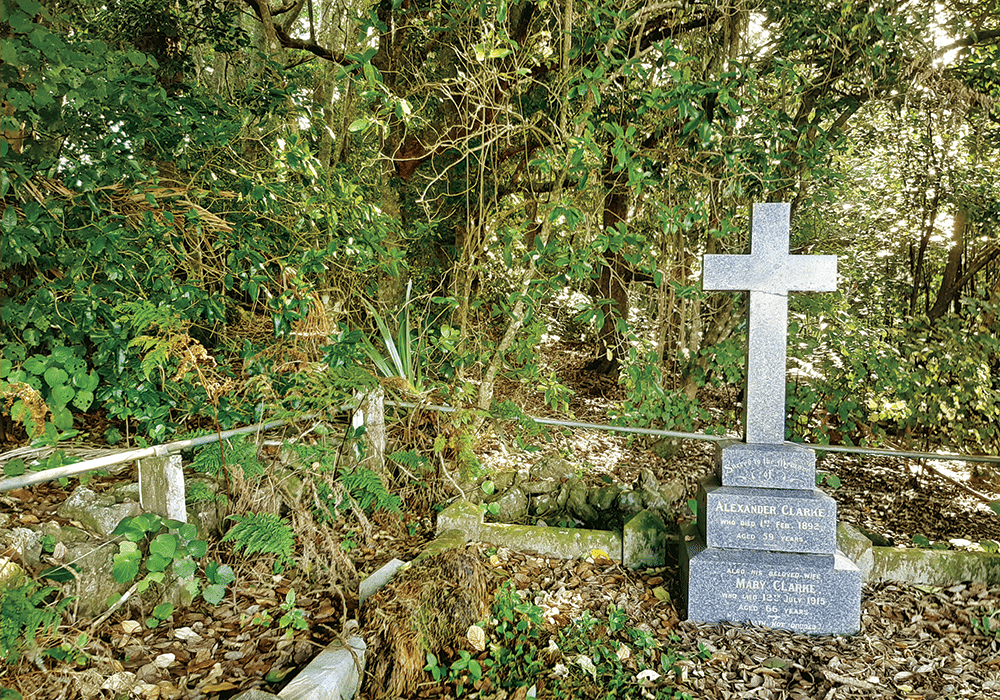

From Millington Bush Station we took a short bush walk that took us to the Clarke family graveyard. The Clarke family owned the property, and farmed it for almost 90 years, until its purchase by the museum in 1972. History buffs will enjoy visiting the colonial Glorat, the Clarke’s family homestead, built in 1885 by Dr Alexander Clarke, a Scots-born former ship’s doctor who brought his wife and three sons to New Zealand in 1884. Modifications can be seen where the homestead had been designed with a surgery, open on a Wednesday from 11am until noon for performing and inspecting vaccinations.

As we walked back beside the railway track we visited some of Kiwi North’s many clubs. At the Rock and Gemstone Club we found crystals for sale, while children worked on craft projects. The Vintage Machinery Club has an array of tractors and farm machinery. Other clubs include the Amateur Radio Club, the Vintage Car Club and the Northland Astronomical Society.

Built Heritage

Very little change was made to Glorat from the early 1900s to the 1970s, when it was taken over by the museum, making it a fascinating place to investigate. Glorat is currently closed for conservation, but Kiwi North’s excellent website has a link for a virtual tour.

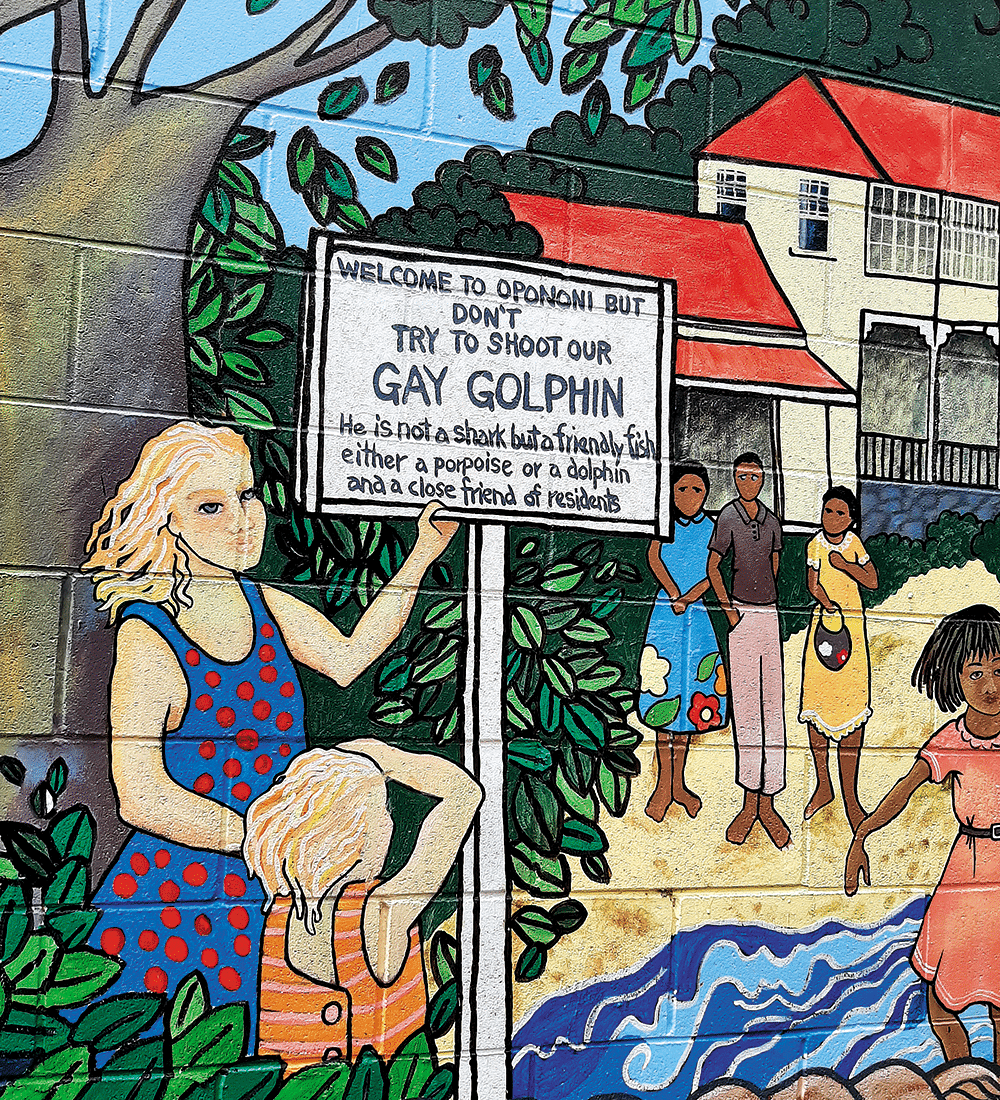

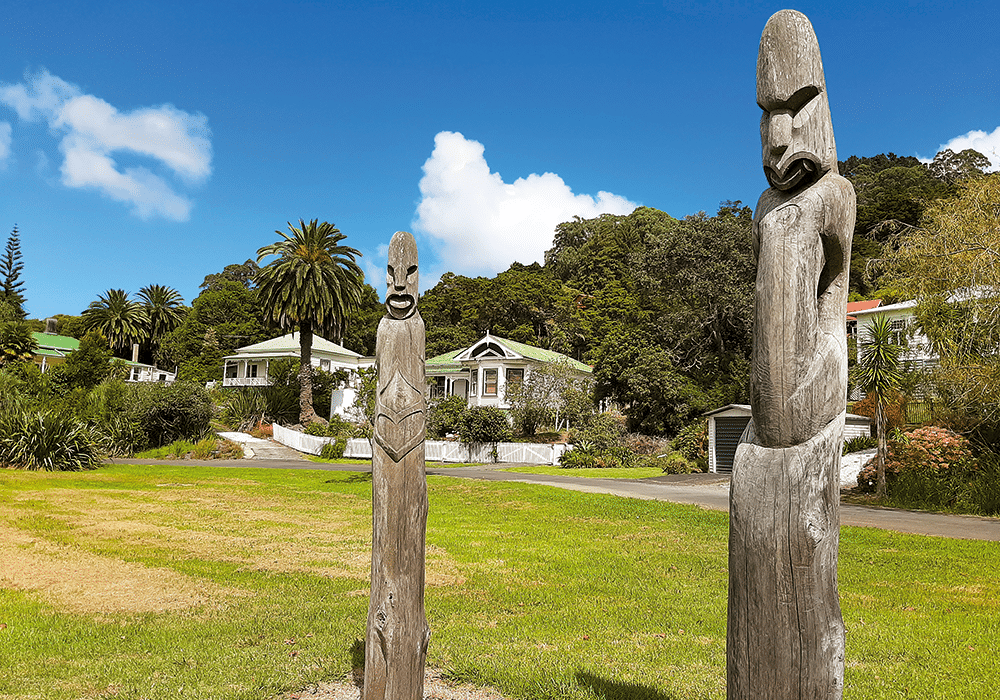

Scattered between the museum and Glorat you’ll find a unique collection of colonial buildings, illustrating Northland history from the 1850s. The Oruaiti Chapel dates from 1859 and is thought to be the smallest hexagonal chapel in New Zealand. It was built from a single kauri log, while the door lock was crafted from a piece of oak brought to New Zealand by a local settler. The pretty building is now used for weddings.

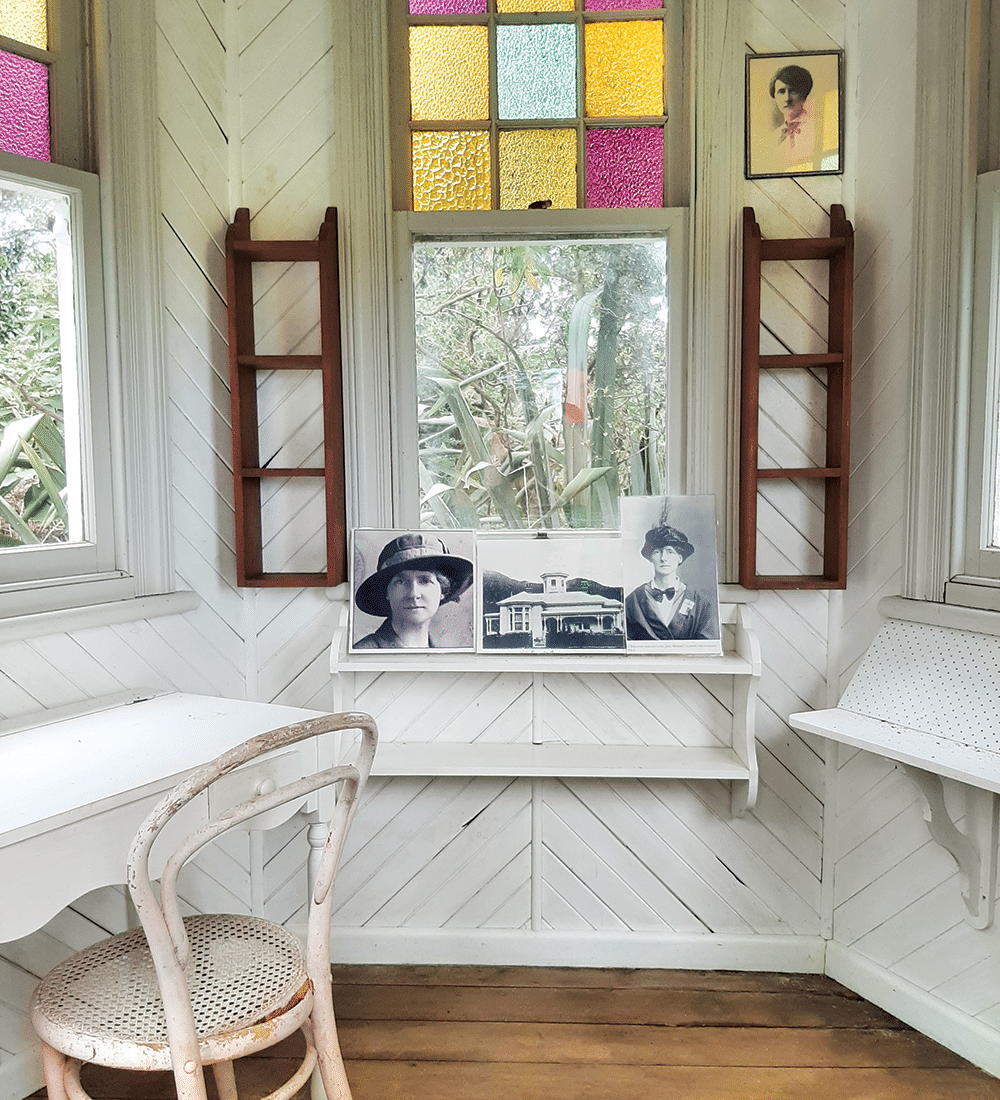

A similar little building nearby was once the turret of the Mander family villa. It was here that author Jane Mander wrote articles for her father Francis Mander’s newspaper, The Northern Advocate. Jane’s most famous novel, The Story of a New Zealand River, was published in 1920. The Whangārei Women’s Jail is another of Kiwi North’s little buildings. Around 1900 it stood in the centre of town, beside a larger men’s jail and the police sergeant’s house.

Children are fascinated by the school building, originally Riponui Pah School, built in 1898. Local students get to dress in period costumes and have a lesson as part of the educational experience provided for schools at Kiwi North. Another glimpse of life in days gone by is the Medical Museum, where visitors can admire (or cringe at) a collection of instruments and equipment.

Bird Recovery Centre

Tucked away beside the museum is the Whangārei Native Bird Recovery Centre. Since its inception in 1991, the centre has cared for tens of thousands of injured birds, from kiwi to albatross. Founded by Robert and Robyn Webb, the centre is run by volunteers who care for the injured birds.

The day we visited there were two kingfishers recovering from damaged wings, and a poor one-eyed tui, who will remain living at the centre as it will be unable to survive in the wild. This tui may live as long as a predecessor called Woof Woof, a tūī who could talk as well as sing and who lived to be 16 years of age.

Beside the aviaries there is a kiwi recovery area and incubation unit. Chicks are raised here before being released into the wild.

More Information

- Kiwi North is at 500 State Highway 14, Maunu, Whangarei

- NZMCA members can book a site at Kiwi North via the app or at reception. Maximum three nights stay. Free showers and toilet facilities. $5 off entry to the Museum and Kiwi House when staying overnight.

- Useful websites: Kiwinorth.co.nz; nbr.org.nz